When 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford walked down the street toward Central High School in 1957, she expected enhanced educational opportunities and increased chances for college scholarships to lie ahead.

What met her was a mob of protesters, angry that nine Black children were attempting to attend school with their white children.

Eckford's family didn't have a phone, so she wasn't informed that the other members of her group -- students who came to be known as the Little Rock Nine -- were meeting with civil rights leader Daisy Bates, and would face the first day together as a group.

The crowd screamed racist taunts, threatened Eckford's life and even spit on the dress her family had made special for her first day of school. In a photograph by Will Counts that went on to international fame, Eckford's back is to the mob trailing behind her. Some scream and threaten her, their faces contorted in anger. All that was on her mind was how to get to the bus stop, which in her head meant safety.

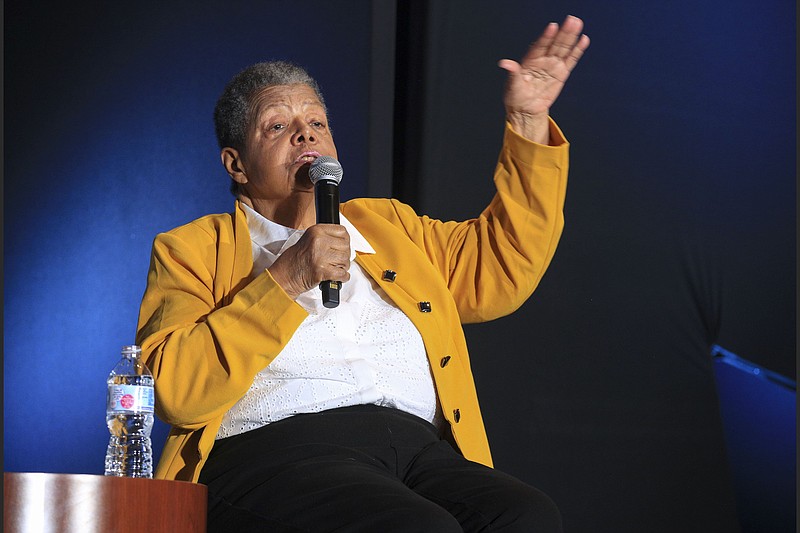

Saturday marked the 64th anniversary of the start of Central High crisis. Recently Eckford, now 79, spoke with the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette via Zoom video chat from the Central High School Museum in Little Rock about her thoughts on the iconic photo; why she chose not to speak about her experience at Central for three decades; and why she is now passionate about speaking with students.

Why are certain details left out of the narrative of the Little Rock Nine's experience?

"For many people, the worst we endured was what we endured on our first attempt to go to school," Eckford says. She adds that part of that misconception was their fault, not sharing the full extent of what they had experienced. The superintendent urged the students not to talk to the press, and it was decided that nothing about what went on inside the schools would be published. The NAACP encouraged the Nine to make it look like desegregation was working. "So we contributed to that. Among the nine of us, none of us talked about what was going on inside the schools for 30 years." Even at home she didn't discuss the verbal and physical harassment she and the other eight students faced, because she knew her mother would take her out of Central, Eckford adds.

What prompted her to begin speaking publicly about her experience at Central High School?

Several factors went into Eckford's decision to begin sharing her true experience at Central. Ultimately, she says, she couldn't bear the revisions that were done to the story over time. She spoke with a Central graduate from the class of 1998 who told her he didn't know much about the school's history.

"In oral history, there's lots of opportunities for people to reframe their memories, so I've been skeptical about it from the beginning," she says. "I thought students would not be able to discern what was real and what was not."

However, she credits The Memory Project, an initiative where students went out and interviewed people regarding what they remembered about the past, for helping them to uncover some history they wouldn't have otherwise gotten in their textbooks.

In the late '90s, two drama teachers from Central tried to put on a play about the Little Rock Nine, and watching a rehearsal, Eckford says she could tell people still didn't understand how much the Little Rock Nine had been set apart and how much they endured. She didn't know it at the time, but what she was doing by talking about her past was immersion therapy. Immersion therapy -- also referred to as "exposure therapy," according to the American Psychological Association -- is a treatment technique used by psychologists to help individuals confront their fears. Exposing a person to the things he or she is fearful of can help them reduce fear and avoidance, the association website reveals.

"That was really painful," Eckford says, choking back tears. "But, that's what helped me tremendously to get through those memories."

What are her thoughts on that iconic photo of her being followed by the mob of protesters?

"It's very ironic to me that people describe this [her stance] as strength. I was frozen. I had to get away," Eckford says.

There are times when she comes upon the photo unaware, and it "really knocks me back. It breaks me apart," she adds. "And there are other times when I see it and I don't feel anything. But I never felt good about that picture."

Now, with the help of an artist rendering by Ajamu Kojo, titled "Wakanda Don't Cry," she has a different response to it. The rendering is a depiction of the photo, but the artist put a spear in her hand. "I have a feeling of empowerment looking at that image, but I don't have that when I look at the original image," Eckford comments.

What is her most painful memory?

Apart from the verbal and physical harassment Eckford and the other eight students faced on a daily basis, the memories that hurt the most are of the people who turned their backs and didn't acknowledge the abuse they saw or heard.

"I think one of the things that people don't know is, when they turn their back and don't get involved, that they are actually making a decision that impacts the person that is being harassed," Eckford says. "I find it very painful [to think] of them. It was probably as painful as the people who organized to knock us about."

Were there white students who were kind to her? What impact did they have on her?

Eckford smiles when talking about two people who made her look forward to class by simply engaging her in ordinary conversation: Ken Reinhardt and Ann Williams. Despite her being shy, speech class was her favorite period of the day, one she looked forward to knowing they were there and would engage with her.

"It was being treated like one of the other students," she says. "It was the acceptance and persistence of contact."

In previous years when she talked about these students, Eckford chose not to name them while their parents still lived in Little Rock; she feared they might face repercussions. Many years later she learned that Williams' father had hired armed guards to stand watch outside their home, while Reinhardt's family received late-night threatening phone calls.

How did she heal from the past?

Up until very recently, Eckford couldn't stand to be in large crowds -- which to her meant anything more than five people -- because of the noise. She would get up, walk away and come back, she says. Recently, at a packed and noisy dinner, she stayed instead of leaving her seat, she recalls. She told herself, "I endured that, I survived that" -- which has become something she repeats to herself when in a similar situation.

Eckford is working on being able to be close to people. "Hopefully it will not be an endurance test," she adds.

What are her thoughts on criticism of classroom lectures and discussions on issues related to social justice?

Eckford believes there's validity in evidence-based history. She says it's a disservice for students not to learn about social-justice issues: "Real change is incremental and doesn't proceed in a straight line."

What does she say to people who say "Politics doesn't belong in schools"?

Schools are all about politics, Eckford says. To her, the act of deciding what curricula and textbooks are used in school is politics.

Why does she feel comfortable opening up to students?

"It's my opportunity to teach without the burdens of actually being a day-to-day teacher," Eckford laughs. She adds that she feels she owes it to students, because it was students who were patient with her; who would wait out the awkward moments that she had.

"I owe a debt to them to have arrived at where I am now," she says.

What can students do to honor and share her story?

Eckford recommends talking to the older members of their families and asking questions. "If they say they grew up with only people of one race, ask them why, because those things don't just happen," she says. She also recommends reading as much as possible and seeking out disparate voices.

What, in her opinion, is the state of Little Rock today?

The medical school, as well as other educational and financial institutions, have improved Little Rock's diversity by drawing people from a variety of backgrounds who bring their families, according to Eckford. However, she doesn't believe Little Rock is more accepting. Until we honestly acknowledge our history, we cannot have real change, she says.

What brings her joy?

Eckford says she enjoys the beauty of her front yard, whose landscape design is maintained by her son. She has a crepe myrtle blooming, bay lilies and drought-hardy plants. Also, she has been a habitual reader since the third grade. Reading, she says, was something she was able to do even when she was at her poorest: She could walk to the thrift store and buy a book for 50 cents.

What books does she recommend?

◼️ "Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right" by Arlie Russell Hochschild. Eckford says sometimes she goes on a quest to understand, rather than just categorize, points of view she feels are opposite to hers. "I feel much better trying to understand them, and that's why I recommended 'Strangers in Their Own Land', because it gives you a basis from their point of view [for] how they arrived at their conclusions," she says.

◼️ "Remember Little Rock: The Time, The People, The Stories" by Paul Robert Walker. "Remember Little Rock" examines how locals framed the crisis versus what actually happened. As Eckford explains, many people's accounts avoid providing specific details about the crisis, which is a way of denying how the students were mistreated.