“May 6, 2004 was the worst day of my life,” Richard Dunlap said, reflecting on his 23 years in service between the National Guard and the Army. “We were in Baghdad, Iraq. We had just been there for 30 days and I remember this because it was just two days before my birthday.”

“We were on a mission, our job was to guard a checkpoint which was a bridge. I tell everyone that was the worst day of my life because we got attacked that day on the bridge which killed my team leader, severely injured my platoon sergeant and I walked away with a busted eardrum and PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder),” Dunlap courageously shared.

His team was hit with a car bomb. Car bombs and other surprise ambush attacks are considered guerrilla warfare. According to the VA National Center for PTSD, it is these urban-style warfare tactics in Afghanistan and Iraq, marked by guerrilla attacks and roadside improvised explosive devices, that may trigger more post-traumatic stress in surviving military members than even conventional fighting.

It is this experience and first hand knowledge of the lasting impact of PTSD that motivates Richard Dunlap to share his story and bring light to something that impacts millions of veterans.

“Veterans are only comfortable talking to other veterans. We need our own support group for each other where we control it. A lot of men feel judged when they go to a therapist. Those services are definitely needed but we need to make sure veterans feel comfortable sharing their experiences,” Dunlap explained.

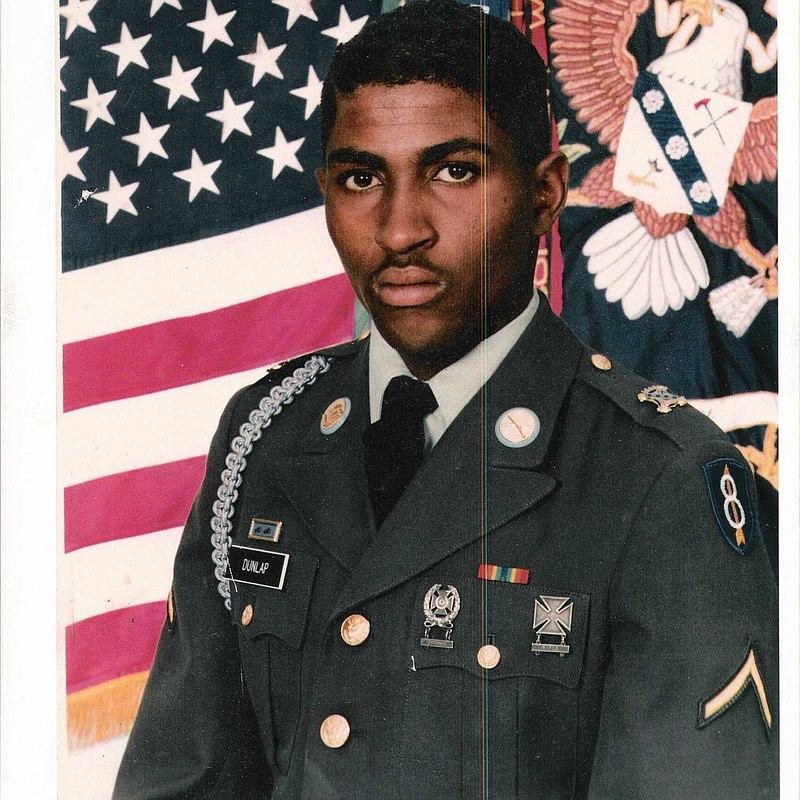

Before becoming an advocate for others in service and for veterans like himself, Dunlap made the decision to serve on behalf of the United States of America.

“Oh that’s a funny story,” Dunlap laughingly said.

“I got in some trouble in high school; teen being a teen. So my eventual mentor, Charles Beck, had on his military uniform and I had never seen someone with a military uniform on before,” Dunlap said. “I literally just walked up to him, started talking and he took it upon himself to start mentoring me. So when I got into a little trouble, he (Beck) looked at me and said, ‘you need to join the military.’”

It was that one sentence by his mentor that became the catalyst for him to join the National Guard in 1986. Dunlap would then transition from the National Guard to the Army in 1988. After finishing his initial duties with the Army, he recalls his mentor seeing him in 1991.

“Charles Beck saw me walking around and he said, ‘all you’re doing is walking into trouble, get back into the military,’” Dunlap said, grinning. “I tell everyone, after that, I never got in trouble again.”

After taking his mentor’s advice for a second time, Dunlap re-enlisted in the National Guard and served from 1991-2014.

Though Charles Beck’s words and advice to Dunlap were simple and oftentimes short and definitive, his advice held a lot of weight with him for a certain reason.

“I came from a single home, it was only my mom and my sister. So I didn’t have that male role model around me all the time,” Dunlap said. “But when I saw him (Beck) with his military uniform on, it opened my eyes; it was shocking.”

Though a lot of the work Dunlap does is around advocating for service members and veterans and sharing some of the ordeals he has experienced and witnessed firsthand, there is also a lot of joy that he recounts from his years in service. While talking with the News-Times, he laughed and joked quite a bit and told a simple story about the power of the human connection, even during his tour in Iraq where there was so much destruction.

“We used to patrol a Baghdad neighborhood and when we did we always took candy. My goodness, the kids over there would make us feel so good,” Dunlap enthusiastically said. “They would run up to us with big smiles and ask for chocolate. So we would look forward to getting chocolate because we knew when we saw those kids, they would give us a smile and ask for chocolate.”

The 51-year old veteran knows the importance of having a human connection and how that connection can help stop one persistent problem for veterans: suicide.

“From the guys I went to Iraq with, I know 12 guys that have committed suicide,” Dunlap shared. “Every year it seems like somebody I went to Iraq with commits suicide.”

Trent Garner, Arkansas State Senator and veteran, recently drafted a letter to the Arkansas CARES Act Steering Committee requesting $50 million in funding to, in part, address services needed to combat veteran suicide, which is estimated to be around 20 veteran suicides a day according to the United States Department of Veterans Affair in their National Suicide Data Report.

Richard Dunlap also has a connection with Trent Garner and the Garner family.

“Trent Garner went to Afghanistan. Trent’s father, Steven Garner, was my first sergeant,” he said.

Dunlap stays pretty busy these days. On top of working with Veterans through Project SOUTH for the past three years as a community coordinator, he has been studying hard to earn multiple degrees. In 2019, he graduated from South Arkansas Community College with a degree in criminal justice and he is currently working on a second degree in media arts entertainment.

He hopes his story will be of help to others and will motivate veterans to know there is a good life waiting for them post-service. He emphasized the importance of human connection, highlighting his connections with his mentor Charles Beck and the adoring children he met in Iraq. He also wants civilians to be more in-tuned and conscious of what veterans face.

“For anyone that is willing to go to Iraq or any battle times, they really do love their country. They are putting their lives on the line for people to sleep comfortably at night,” Dunlap said. “Some people don’t know, they can be in the store and standing next to a veteran. The best thing you can do once you find out someone is a veteran is to thank them for their service. It really goes a long way in making us feel appreciated.”